Why "The Green Hell"?

Writing about the Amazon rainforest, with a different focus...

Because better than any other the phrase Green Hell calls forth a certain vision of the Amazon rainforest. It’s not my vision. And it’s not a familiar vision, at least not to most of us who read the better papers and the upscale journals and worry about things like global warming and biodiversity loss and climate tipping points and looming resource wars over water.

For us, the Amazon is a great ark of biodiversity, or the world’s largest carbon sink, or the lungs of the planet, or simply the last intact ecosystem on earth still untouched by humanity and its works. In the moral sphere, thoughts about the Amazon come bounded within circles labelled ‘Threatened’ and ‘In Need of Preservation.’

Our images, when we picture the Amazon, are of towering trees with buttress roots and hanging vines, sloths contentedly munching on an eternity of dark green leaves, indigenous peoples with painted faces making a living as their ancestors have from bow and arrow and careful conservation of the forest. We see Blu the Spix’s Macaw, urbanized and alienated in the American suburbs, rediscovering his true self in the bosom of the forest. We see Neytiri and the Na’vi defending Pandora from the greedy imperialist fucks blasting the world tree in a stupid search for unobtainium.

This list is hardly comprehensive. Any one reader could add or subtract to it, quibble or criticize or take total unrestrained umbrage with one or another of the items and their inclusion or placement on the list. Feel free, if that’s your pleasure, though I mean to avoid that discussion myself. Nor do I really mean to criticize this vision, which I happen to share, except to point out one salient and often forgotten fact:

It’s not a vision with much traction on the people actually living in the Amazon.

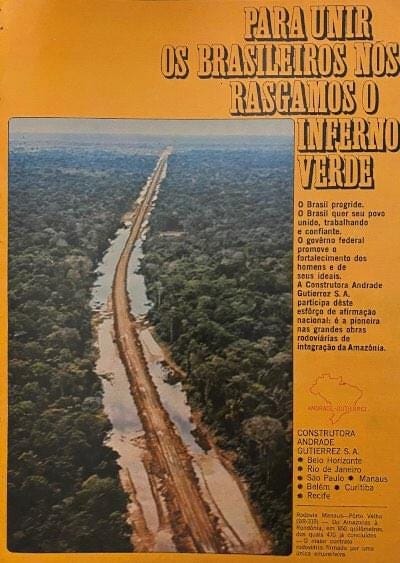

For Amazon residents – particularly Brazilian Amazon residents – the Amazon is a frontier, similar to the American West, a place that needs developing, civilizing, and dare I say it, conquering. It’s a vision strikingly captured in these posters dating back to the ‘60s and ‘70s, the years when Brazil’s military government began it’s drive north into the Amazon.

“To Unite Brazilians, We Tore Open the Green Hell” reads the first one, over a photo of the TransAmazon highway.

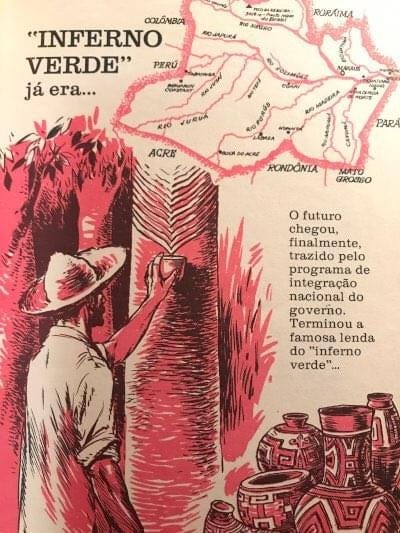

“The Green Hell is Over”, reads the title of the second.

The phrase “Green Hell”, Inferno Verde in Portuguese comes from a 1908 book by Alberto Rangel, a military engineer turned writer who served for a time as the director-general of the department and Land and Settlement in the Amazon. Like Che’s book about his guerilla efforts in Africa, it’s a story of failure at every turn. Rangel got nowhere and accomplished nothing, and retreated to a sinecured life in Brazil’s foreign service. Green Hell seems to have cemented the idea, at least in Brazilian ruling circles, that the Amazon was a land of pestilence and disease, unfit for human habitation.

For the military government that took power in Brazil in a 1964 coup, their own legitimacy rested largely on their view of themselves as modernizers, capable technocrats who could and would drag Brazil forwards into the modern era. The subtitle of the second poster capture this vision: “The Future has finally arrived, brought by the government’s program of national integration. It’s the end of the famous legend of ‘the Green Hell’.”

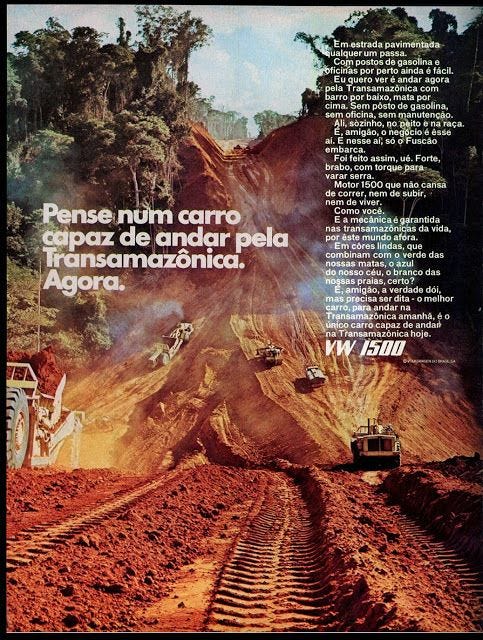

The generals carved highways through the rainforest and encouraged settlers to move there, promising a new and modern life of plenty. The third poster captures this vision. It’s an ad for the new VW 1500 placed in a Brazil’s big newsmagazine, Veja. “Imagine a car that can travel the TransAmzon Highway. Today.” From Green Hell to conspicuous consumption in one generation.

Here’s the car that could do it.

When the developed world discovered what Brazil was up to in the Amazon in the 1980s it was collectively appalled. Sting and a million documentary makers arrived to sing and film and chastise. The military government itself, discredited by scandal and debt and economic mismanagement, came to an ignominious end in 1989. Three years later the city of Rio de Janeiro hosted the first Earth Summit and gave its name to the legally binding Rio Convention covering biodiversity and climate change.

Though possibly forgotten in the rest of the world, the Earth Summit marked a watershed in Brazil. In government agencies, in the elite media, in universities, environmental preservation became the official policy. This new consensus found expression in dozens of laws and regulations concerning the Amazon and its preservation and settlement: laws regarding acceptable levels and types of deforestation, laws regarding parks and reserves and protected areas, laws regarding Indigenous reserves, laws regarding mining, laws regarding biodiversity and endangered species. Taken together, these laws and regulations and the institutions to enforce them comprise perhaps the finest set of environmental protections ever devised by any nation on earth. They enshrined a vision of the Amazon as a unique place in need of preservation, a place where man must tread lightly or perhaps not at all.

Alas, the people who had moved to the Amazon, and their children, and the people who moved there later – none of them ever really got the memo. For them the vision remained that of the frontier, the place to fill and subdue, a green hell in need of taming.

At some level, often not far beneath the surface, every conflict in the Amazon is a duel between these two visions. A battle between Team Pandora and Team Green Hell. And that is what I plan to write about in this newsletter. I am by nature and training more of a journalist than an essayist. Expect more on-the-ground reporting than erudite musings.

Also, I plan to focus my efforts on Team Green Hell. It’s not that share or support their vision – I don’t. But Team Pandora already has, well, just about every Western paper and journal there is to document their doings; they hardly need my help.

As for the Green Hell side, I come not to praise them but neither am I pulling out the shovel. I can’t help but cling to the naïve hope that via an honest inquiry into their side of the story, we might actually find some common ground.